As my last blog post discussed the political grievances between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan regarding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), this post will look further into how political cooperation between the Eastern Nile countries may not be as clear cut as first imagined.

In fact, economic cooperation between Ethiopia and Sudan, despite their failure to find common ground on water cooperation has been thriving in the last 10 years (Tawfik, 2019). With the backdrop of the signing of the Declaration of Principles (DoP) on the GERD in 2015, there was renewed hope among everyone in the 3 Eastern Nile countries that cooperation on not just water, but all other resources rooted in the water sector such as food, energy and trade would be progressive too (Tawfik, 2019). However, is it possible for that to happen when even the fundamental resource that is contained in the other resources, water, is so difficult to come to an agreement on itself?

Rawia Tawfik in her article explains that cooperation on resources beyond water, also entirely depends on national countries and the interests of individual governments. That they will do their own assessment on what the possible benefits and drawbacks will be from possible cooperation and then come to the decision to work together (Tawfik, 2019). This is why it could be argued that Egypt refuses to cooperate on the GERD, as they see more drawbacks to the project than any possible benefits it brings to them. Even with the possibility of Ethiopia exporting hydropower to Egypt through the GERD, officials have refused to accept it until an agreement on the actual filling and operation of the GERD is first settled (Tawfik, 2019). If Egypt was fearful of their waning water supplies due to the GERD, they should be open to investing in Sudan’s and Ethiopia’s agricultural sector and benefit from the green water (rainwater absorbed into the soil) imports through that (Tawfik, 2020). Currently, that does not seem to be an option as Egypt continues to find ways to find a solution to the GERD first.

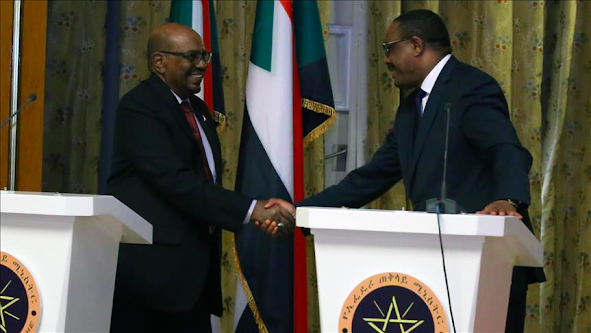

However, this is not the case for Ethiopia and Sudan, where their disagreements on some aspects of the GERD and water cooperation has not affected cooperation on resources in other sectors, and their economic cooperation has significantly improved (Tawfik, 2019). Although it can be argued that other resources and sectors are probably easier to come to an agreed understanding to, while resources such as water and oil are the ones that are more likely to create conflict and dispute as their operations lead to large scale projects to extract them (Tawfik, 2020).

This example in the Eastern Nile Basin can be used to highlight the complicated relationships between countries and how cooperation on managing resources is not as easy as one would expect. That the notion water cooperation will lead to economic cooperation and managing resources equally in other sectors is not true, as seen by the examples of Egypt and Sudan. Water and the hydropolitics behind it are very complex so it’s no surprise that finding a joint solution is difficult compared to coming to a mutual agreement on other resources.

ReplyDeleteThis feedback covers the last three posts transboundary water politics of the Nile basin. These posts have been well presented, showing good engagement with the literature and the focus on a case study while exploring different perspectives is great. My only suggestion will be to give some historical hegemonic context in relation to water management in the Nile basin. The GERD has emerged to alter water distribution but also power in the Nile Basin.

Thank you for your suggestion, have made sure to include historical contexts in my last few posts.

Delete